By Will McCarry

December 4, 2023

With new discovery, island nation turns page on a painful legacy

8 min

By Will McCarry

December 4, 2023

8 min

Nathan Conaboy’s day had taken an unexpected turn, and he now found himself in a distant cavern, searching for geckos.

He and a band of scientists had set out one morning in August to survey wildlife. When monsoon rains washed out the road they were traveling on, the team decided to make the most of it — and stay dry — by poking around a nearby cave they had initially not planned to visit.

Conaboy, a conservation biologist with Conservation International, had joined the expedition to Timor-Leste — a small island nation nestled between Australia and Indonesia that is home to some of the least studied ecosystems on Earth.

The journey was the first of its kind in many years — and turned up a fortuitous find.

At the cave’s entrance, Conaboy — alongside scientists from Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and Timorese officials — passed through a low arch, adorned with patterns painted by prehistoric artists from a millennia ago. He had stepped into a secluded offshoot of an extensive cave system known as Lene Hara, renowned for its archeological significance. As he ventured further, human faces carved into the stone peered at him from across the ages.

Prehistoric artists etched human faces into the walls of the Lene Hara cave system a millennia ago. © Nathan Conaboy

“The passage gradually expands into this bulbous chamber,” Conaboy said. “It was easy to imagine people once living there in the ancient past.”

But Conaboy was not there for a glimpse into the lives of ancient people, instead fixating on the bats swirling above and spiders crawling around his boots on the cave floor. Chan Kin Onn, a herpetologist from the museum, saw something else: a gecko skittering across the limestone.

Onn wedged himself between the rocks and lunged. It was a near miss. But Onn had a hunch that the gecko might be a species new to science.

The team decided to go back to the cave later that night, when geckos are most active.

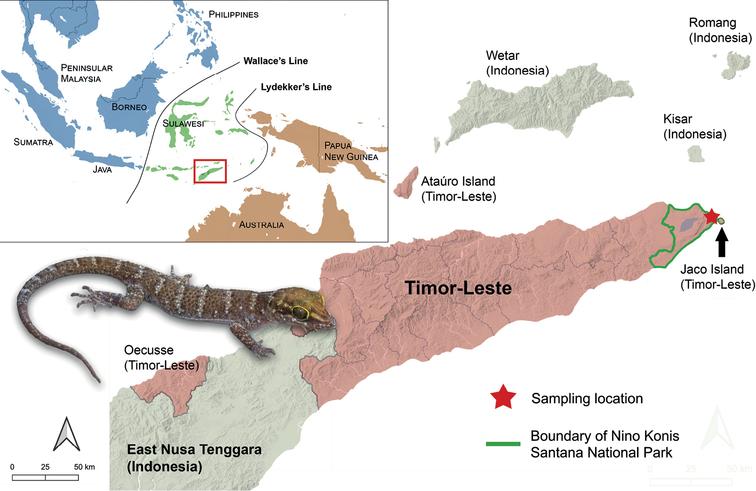

Led by flashlight, they traversed the cave, eyes locked on the ground. Within an hour, they saw unmistakable, darting shapes — 10 individuals of a previously unknown species of bent-toed gecko. The team named it Cyrtodactylus santana in tribute to Nino Konis Santana National Park, where the encounter took place.

The new species of bent-toed gecko was found in the Lene Hara cave system. © Tan Heok Hui

The gecko's new name held added significance as one of the expedition’s Timorese team members was the nephew of the park's namesake — Nino Konis Santana, a revered war hero in the nation's long struggle for independence.

As remarkable as the gecko's discovery was, it signified something more: a fresh approach to conservation in a nation historically marked by foreign intrusion and exploitation.

An evolving history

Nestled between Australia and Indonesia, Timor-Leste is one of the world’s youngest countries. Its name, derived from the Indonesian, Malay and Portuguese words for "east," reflects a history marked by diverse cultures and colonization.

But even as the nation’s modern era has been defined by outside influence, its biodiversity was formed through isolation. Deep-water straits have separated Timor-Leste from the continental shelves of Asia and Australia for millions of years, giving rise to numerous species found nowhere else on the planet.

Timor-Leste is on the southern edge of Southeast Asia's Wallacea region — a cluster of ecologically unique islands named in honor of the Victorian-era naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection.

Timor-Leste is part of Wallacea, a region known as a living laboratory of evolution. © Chan, Grismer, Santana, Pinto, Loke, Conaboy

Like his contemporary Charles Darwin’s famous voyage to the Galapagos, Wallace's explorations across Timor and neighboring islands ignited his pathbreaking work.

“To this day, Wallace represents our baseline scientific understanding of this part of the world. He spent so much time here and discovered so many species,” said former Conservation International expert Frances Loke, who also joined the expedition.

But much about Timor-Leste has changed since. After 500 years of Portuguese colonial rule, the country fell under Indonesian control from 1975 to 1999 before eventually gaining its independence and becoming a democracy.

Still, its past left a legacy.

“Timor-Leste has experienced a long history of colonialism that not only affected the kind of nature that we see there, but also the kinds of structures in place to study and protect nature,” Loke said. “For years the country has been plagued by what we call ‘helicopter science’ — international scientists going in and paying off local guides, extracting specimens without any proper authority or due credit for local communities.”

Perhaps the most controversial example of this unfolded in 2011, when a team from the Australian National University in Canberra chanced upon two fragmented shell fishhooks within a limestone cave in the island's northern region. The hooks traced their origins to the period between 21,000 and 16,000 BCE and then represented the earliest known fishhooks in existence.

“These artifacts were taken from Timor-Leste with very limited or no approvals,” Conaboy said. "And the Timorese people are unable to access them because they are stored away in an Australian museum."

Clouds drift and shadow the rocky shores of Timor-Leste. © Conservation International/photo by Yasushi Hibi

By 2020, the Timorese government put a full stop on scientific research involving the removal of artifacts and specimens from the country. Conservation International spent years working to find a way for new research to continue through proper channels.

“From the very start, we wanted to stress the importance of Timor-Leste asserting its ownership and guardianship over its biodiversity,” Conaboy said. “At the same time, there’s a widely recognized acknowledgment that Timor-Leste lacks the necessary facilities to store what are known as holotypes — specimens that scientists carefully choose to represent the primary example of a newly discovered species.”

In August 2020, the Timorese government and Singapore’s Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum struck a research partnership — with the museum now serving as a regional hub for housing and preserving specimens from Timor-Leste.

"The scoping expedition really marked the inaugural journey under the agreement,” Conaboy said. “It represents the beginning of a genuine and mutually advantageous partnership — one that respects Timor-Leste's history and can contribute to shaping its future."

Now that the gecko’s holotype has made its way into the collection at Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, the team is planning to return to Timor-Leste for a larger, more comprehensive expedition.

“We have to make the case for conservation now,” Loke said. “Otherwise, these ecosystems could be destroyed before we even know what species are there.”

Will McCarry is a staff writer at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.

Join our community

Hear from scientists and changemakers, step into stories of experts in the field, and come closer to the awe-inspiring power of nature. By subscribing, you agree to our terms of use.