By Kiley Price

October 21, 2022

Meet a scientist: Using tech to advance wildlife conservation

8 min

By Kiley Price

October 21, 2022

8 min

Growing up in the bustle of Bogotá, Jorge Ahumada — a self-described “city kid” — rarely ventured into the Colombian countryside. But his family loved watching the nature documentaries of the legendary marine explorer Jacques Cousteau.

What began as an interest in sea creatures eventually transformed into a love for lush green forests — and a career centered on protecting their biodiversity.

Now, as Conservation International’s senior wildlife conservation scientist, Ahumada uses technology to track wildlife species around the world and ensure the data is available to craft smart policies for their protection.

Conservation News spoke to Ahumada about how he moved from watching animals on TV to studying them in the field — and his passion for mining wildlife data to uncover hidden trends in nature.

Question: What was it about Jacques Cousteau’s documentaries that sparked a passion for nature?

Answer: My dad and I used to record those documentaries on our Betamax cassette player and watch them over and over. The deep-sea world that Cousteau explored captured my imagination — not to mention the scuba gear, underwater cameras and other cool gadgets he used.

At a young age, I decided I wanted to become a marine biologist, but my father thought studying biology more broadly would be more practical — and I’m glad he pushed me in that direction.

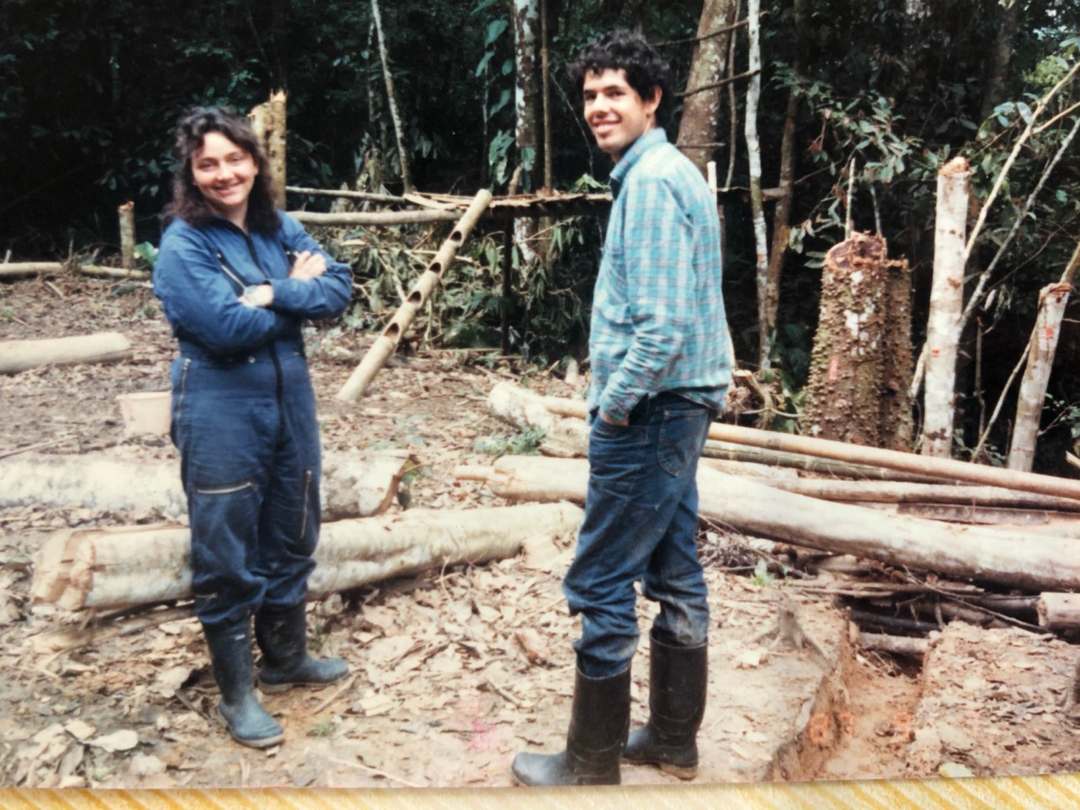

Ahumada as a student working in the Sierra de la Macarena, Colombia. (© Jorge Ahumada)

Q: Why’s that?

A: During my third year in college, I had an opportunity that changed my life: One of my professors led us on a field trip to a remote region of northern Colombia to study birds and plants. I had never been to a tropical forest before. And as we trekked into it, I felt like I was stepping into a cathedral. I was a city kid; I had never seen anything so full of life — and it filled me with a sort of reverence. The humid smell, the sounds of frogs, the colorful birds… I was struck by the abundance of it all. From that moment on, I knew I wanted to become a field biologist.

At the end of my undergraduate program, I traveled to Colombia’s Amazon rainforest, where I lived in a camp off and on for three years while researching spider monkeys. They’re fascinating creatures, but very hard to keep up with as they move through the trees. Craning your head to track them in the canopy can quickly lead to throbbing neck pain.

A few years later, while working on my doctorate, l had an “aha” moment. I realized I could combine field work with math and theoretical ecology to understand and predict animal population trends. From then on, I would go into the field to gather wildlife data and return to my lab to run simulations and computer models to determine why populations of certain species were growing or declining. It was like unlocking the secrets of the forest.

Q: How did that lead you to Conservation International?

A: After spending some time as a population ecology professor in Bogota and as a post-doctoral researcher in Georgia and Wisconsin, I joined Conservation International in 2006 to help run the Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring Network, known as TEAM.

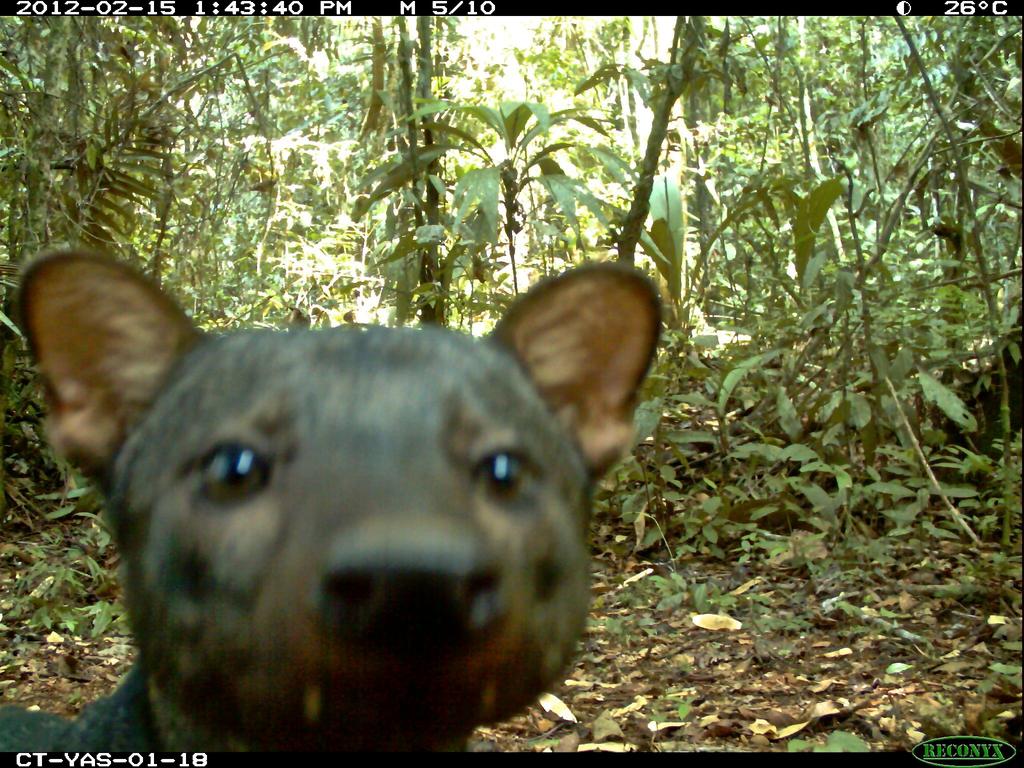

It was a partnership, formerly led by Conservation International, that placed motion-detector cameras, known as “camera traps,” in tropical forests around the world. Over 12 years, TEAM collected millions of photos of wildlife — from curious chimpanzees in Congo to rare bush dogs in the Peruvian Amazon — which helped inform policies for wildlife conservation.

Over time, however, I realized there was a downside to having all this data: Most of it wasn’t being shared.

Researchers at the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in Uganda set up a camera trap. (© Benjamin Drummond)

Q: What do you mean?

A: Camera traps have made it very easy to collect huge amounts of data about wildlife, but most of those images are simply stored in people’s computers and databases. There was no central repository for researchers to compile global data and analyze it — so I decided to make one.

In 2019 Conservation International, Google, and a group of partners launched a platform called “Wildlife Insights,” which allows researchers to easily view, share and explore camera-trap data. Our platform currently houses more than 50 million images. And because it uses artificial intelligence to identify the animals in the images, it can extract, organize and analyze data in minutes. It used to take months to do that.

Q: But aren’t animals disappearing at rapid rates? You must not be seeing that many.

A: You’re not wrong about the world’s biodiversity being in trouble. According to UN reports, more than 1 million species could be at risk of extinction if we don’t scale up conservation efforts. But there have not been sufficient tools to adequately track wildlife populations until now. The next few years of tracking through Wildlife Insights will provide data to show us how bad the problem really is — and what we need to do to fix it.

Q: Data and technology are shaping our lives, how do you see them supporting conservation?

A: They’re absolutely critical. My career has focused on finding ways to increase the amount of wildlife data available for conservation — and develop the technology to analyze and make it actionable.

We gather an enormous amount of climate data on the ground and from satellites, but data on biodiversity is much more limited. The climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are two sides of the same coin; you can’t solve one without the other. Without more data on wildlife — which provides indicators of overall ecosystem health — we won’t know if the solutions we implement to stop the climate and biodiversity crises will be effective enough in the long term.

We need to think bigger in terms of developing tech to diagnose nature’s health and capture the entire array of organisms that contribute to it so we can better understand, conserve and restore it.

A camera trap captures an image of the elusive short-eared dog, Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. (© TEAM Network)

Q: Are you hopeful for the future of wildlife around the world?

A: Yes, I’m hopeful because I’ve seen how resilient nature can be. Many ecosystems are adaptive and robust. If we take the pressure off habitats like forests and mangroves, animals can come back faster than we think. Take Australia: the bushfire season of 2019–2020 scorched millions of hectares, killing or harming 3 billion animals. At the time, it was difficult to imagine life ever returning to that region. But data from camera traps in New South Wales shows animals are in fact returning. With a little help, nature does bounce back — we just need to give it that chance.

This short documentary film tells the story of a camera trapper at Colombia’s Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute who is using Wildlife Insights to document and preserve the biological diversity in Caño Cristales, the country’s remote upper Amazon region. Watch the film here.

Kiley Price is a former staff writer and news editor at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.

Cover image: Jorge Ahumada on the Potomac River in Virginia. (© Jorge Ahumada)

Join our community

Hear from scientists and changemakers, step into stories of experts in the field, and come closer to the awe-inspiring power of nature. By subscribing, you agree to our terms of use.