By Mary Kate McCoy

March 20, 2024

Biologist’s keen eye spots (another) new species in the Pacific

3 min

By Mary Kate McCoy

March 20, 2024

3 min

Diving in the waters of Samoa, Mark Erdmann watched as a haze of colorful little fish — each no bigger than a raisin — hovered over a coral reef, nearly motionless to avoid predators.

With the dazzling diversity of species that live on a coral reef, Erdmann, a Conservation International marine biologist, might have easily overlooked the dwarfgobies. To the untrained eye, they are nearly indistinguishable from dozens of similar species. But he glimpsed something new on the little fishes: a red stripe across the top of the heads and a pattern of white spokes radiating outward from the pupils.

He snapped a picture.

Photo by Mark Erdmann

Eviota taeiae.

“I immediately recognized it as a different species,” he said. “The satisfaction of recording another new species is the ultimate dopamine hit.”

It would take eight years to confirm Erdmann’s finding — delays in gathering data samples are not unusual when documenting a new species. But last fall genetic testing finally verified that he had discovered his 184th new species. He and his colleagues named it Eviota taeiae in honor of biologist Sue Taei, who led Conservation International’s programs in the Pacific islands for nearly 20 years and championed Polynesia’s communities and marine ecosystems before her passing in 2019.

For his many marine discoveries, Erdmann credits a special skill:

“I have a photographic memory, which serves me very well in this field,” he said. “I basically have a catalog of all known reef fish species in the region squirreled away in my mind, which helps me recognize in the moment if I’ve come across something new.

Known as the “rice of the reef,” dwarfgobies are critical to reef ecosystems; nearly every other reef fish snacks on them for food. Their lifespans are short, a mere blink-and-you’ll-miss-it nine weeks. And that’s exactly what has made the dwarfgoby the most diverse of all fish genera — with 132 species known to science, and likely far more yet to be discovered.

The hidden richness within the genus stems from their uniquely small range. While they don’t travel far during their lives, occasionally groups will get separated and drift off in ocean currents. Those that break off establish a new colony that goes in a different genetic direction and develops unique characteristics, typically in the form of color variation. Over time, this leads to a new species.

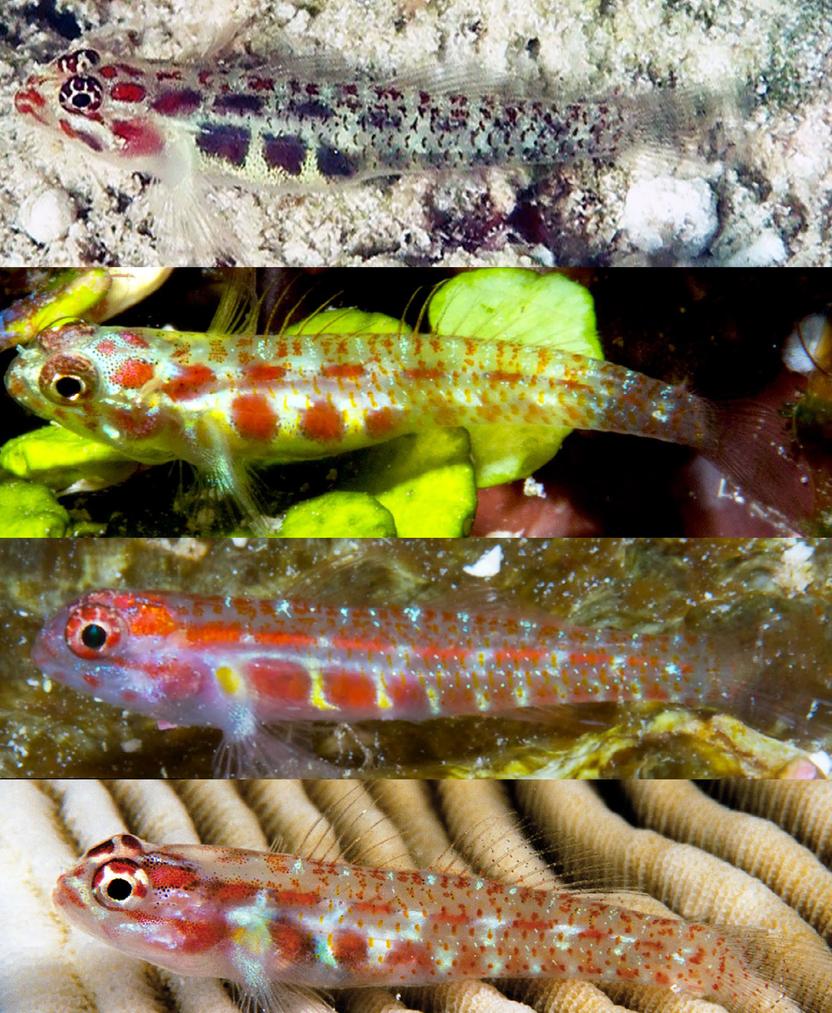

© Journal of Ocean Science Foundation

Assorted dwarfgoby species, top to bottom: Eviota guttata, E. teresae, E. taeiae and E. albolineata. Photo collage by David Greenfield, with individual images (top to bottom) by J. Casey, M. Erdmann, M. Erdmann, and P. Bacchet. Image used with permission from Journal of Ocean Science Foundation.

While there may only be subtle visual differences between different dwarfgoby species, genetic testing shows that often millions of years of evolution separate them, Erdmann said.

“They’re just constantly evolving — if you move from Indonesia to Fiji to Samoa, you’re going to get different species of dwarfgoby in each place you go,” Erdmann said. “We’re only just now beginning to realize how small many dwarfgoby ranges are and what that could tell us about evolution in the sea.”

Despite having discovered and named many species, the rush of identifying a new one never fades for Erdmann. Every new discovery is a bright spot — a bit of good news, juxtaposed against the seemingly endless reports of Earth’s dwindling biodiversity.

“For many people, it’s almost unbelievable that we’re still discovering new species in 2024,” he said. “But there’s still so much we don’t know about our planet. We need to work doubly hard to protect it because we’re losing species we didn’t even know existed.”

Mary Kate McCoy is a staff writer at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.

Join our community

Hear from scientists and changemakers, step into stories of experts in the field, and come closer to the awe-inspiring power of nature. By subscribing, you agree to our terms of use.