By Kiley Price

August 30, 2019

Deep dive: New findings from our whale shark watchers

6 min

By Kiley Price

August 30, 2019

6 min

In the crystal-clear waters of Cenderawasih Bay, in the Indonesian province of West Papua, two researchers spend their days chasing down one of Earth’s most mysterious creatures: the whale shark.

For Abraham Sianipar and Mark Erdmann — Conservation International scientists and world experts on whale sharks — studying the planet’s biggest fish involves tracking their long-distance trips across the Pacific, understanding the challenges they face in a rapidly changing climate — and diving deep into their complicated relationship with humans.

On International Whale Shark Day, the scientists shared their latest discoveries with Conservation News — including a grave threat to the survival of these enigmatic giants.

Question: What does a typical day of whale shark tagging look like?

Sianipar: Well, our “normal” day is actually quite unique. When we first started working in Cenderawasih Bay, we discovered that bagan fishers (fishers that use lift nets over a large platform) often accidentally catch whale sharks in their nets while they are fishing for silverside baitfish — which are coincidentally one of the whale shark’s favorite foods. We realized that this interaction gives us a rare opportunity to learn more about the whale sharks up close, while they are unable to quickly swim away.

Now, our whale shark tagging expeditions involve picking out a specific shark that we want to tag, catching it in the bagan net and attaching a satellite tag to its dorsal fin that will track its movements for the next two years. After the tagging is complete, we gently release the whale shark from the net so that it can swim freely about the bay. We rely on the bagan fishers’ willingness to help us and, luckily, they always see the whale shark as a good omen, rather than an annoying pest.

© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann

A bagan fishing platform in West Papua, Indonesia.

Erdmann: Of course, the immediate question that arose as we considered this process was whether it would stress out the fish. Back in 2017, Conservation International worked with the Georgia Aquarium to perform a health assessment on the whale sharks before and after the tagging, and their blood samples showed no signs of significant stress. When you are underwater, you can tell that they are a little annoyed when they first get stuck in the net, but then they lay on the bottom of the net like it’s a big hammock — with an all-you-can-eat buffet of silverside baitfish right in front of them.

Q: What is your latest research showing you?

Erdmann: Although the whale shark is the world’s largest fish, we still don’t know that much about it. With our research, however, we are learning more about them every day. Using this method that takes advantage of the bagan nets, Conservation International is one of the first organizations to be able to measure a whale shark down to the exact centimeter. The length of a whale shark correlates directly with its age, so we are using these measurements to learn more about their life spans — most are thought to live more than 50-60 years!

© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann

Whale sharks can grow up to 18 meters (60 feet). A researcher swims with a whale shark in Indonesia.

To make sure we can follow these whale sharks past their “teen years,” we are actually working with a global whale-shark database called “Wildbook for Whale Sharks.” Researchers from all around the world can submit photos of the sharks they are tracking and if one of our sharks happens to show up in Australia or the Galápagos Islands, then we will automatically be notified. Our goal is to collaborate with partners that work around the Asia-Pacific region to develop a comprehensive photo identification database for all of Indonesia.

Sianipar: After running this whale-shark tagging program for five years, we have also identified some interesting trends with whale shark migration patterns. Whale sharks in Cenderawasih Bay tend to live there year-round, but some individuals journey out into other parts of the Pacific. The most intriguing thing is that although they always come back, they will repeat this behavior every year.

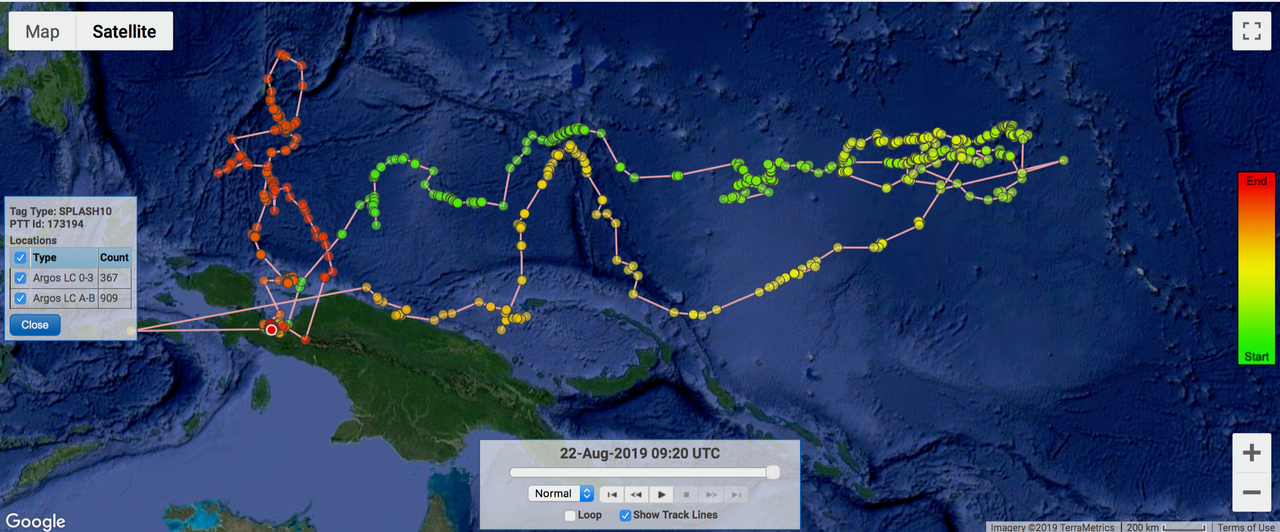

© Conservation International

Data shows that one of the whale sharks travelled over 23,000 km (14,290 miles) in just 14 months.

Q: If they have an almost endless supply of food, why are some sharks leaving the bay?

Erdmann: We are still trying to answer that question. Animal migration is metabolically expensive — meaning it takes a lot of energy for them to move long distances. There are only two real reasons a shark would migrate: To find food or to find a mate. All of the whale sharks we study in Cenderawasih Bay are juvenile males, meaning they are too young to mate.

Sianipar: If the sharks have plenty of food and are not mating, what would make them leave the bay? This is the mystery we hope to solve by developing a more advanced fin-mount tag, which will enable us to get more details about the whale shark’s behavior through new sensors and even a camera.

Q: Do the local communities ever interact with the whale sharks?

Sianipar: Of course! If you speak with the villagers, they can’t remember a time when the whale sharks were not swimming in the bay. We’ve long focused on trying to develop marine tourism in some of these areas, as an alternative to fishing being the sole source of income for many community members. A study done in 2017 showed that whale shark tourism and visitors to the surrounding area amounted to almost US$ 2.6 billion in Cenderawasih Bay National Park alone, meaning the world’s biggest fish is also big business for local communities.

We are actually working with the government, scientists, universities and other stakeholders to develop two national regulations on the best ways to manage whale shark tourism. We just helped set up a sustainable, community-based ecotourism program in Saleh Bay, outside of Bali.

© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann

Whale shark tourism is now an essential part of West Papua’s economy.

Q: It sounds like the whale sharks in Indonesia are completely safe — unlike many other species of shark.

Sianipar: Although whale sharks are a protected species in Indonesia, they still face many environmental threats. Their migration patterns often overlap with shipping lines and major fisheries, resulting in them being accidentally killed or directly targeted by illegal fishers. Our research helps track their movements and will show how they interact with these massive fishing vessels, which will be useful for guiding conservation strategies within the next six months, including where to set up marine protected areas.

Erdmann: Another critical concern for whale sharks right now is microplastics. In the ocean, the biggest fish often feed on the smallest things, like plankton or baitfish. Whale sharks are filter feeders, meaning they go around and suck in huge quantities of water to filter out food, and are likely to accidentally suck in the small microplastics, too. Conservation International has a research program planned to look at exactly what is going on with these microplastics and how it will affect these massive animals.

© Conservation International/photo by Mark Erdmann

As filter feeders, whale sharks are especially vulnerable to ingesting microplastics.

Abraham Sianipar is Conservation International Indonesia’s Elasmobranch Program Manager. Mark Erdmann is Conservation International’s Vice President of Asia-Pacific Marine Programs. Kiley Price is a staff writer for Conservation International.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.

Join our community

Hear from scientists and changemakers, step into stories of experts in the field, and come closer to the awe-inspiring power of nature. By subscribing, you agree to our terms of use.