The United Kingdom's highest concentrations of irrecoverable carbon are found in the Scottish peatlands, or bogs, where carbon steadily builds in the soil across a 2 million hectare (5 million acre) stretch of waterlogged land. The region's cool, wet, oceanic climate creates conditions for bog mosses and other plants to break down very slowly, storing carbon — and entombing the fossils of large mammals — over thousands of years.

“Irrecoverable carbon” refers to the vast stores of carbon in nature that are vulnerable to release from human activity and, if lost, could not be restored by 2050 — when the world must reach net-zero emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Learn more about this critical research.

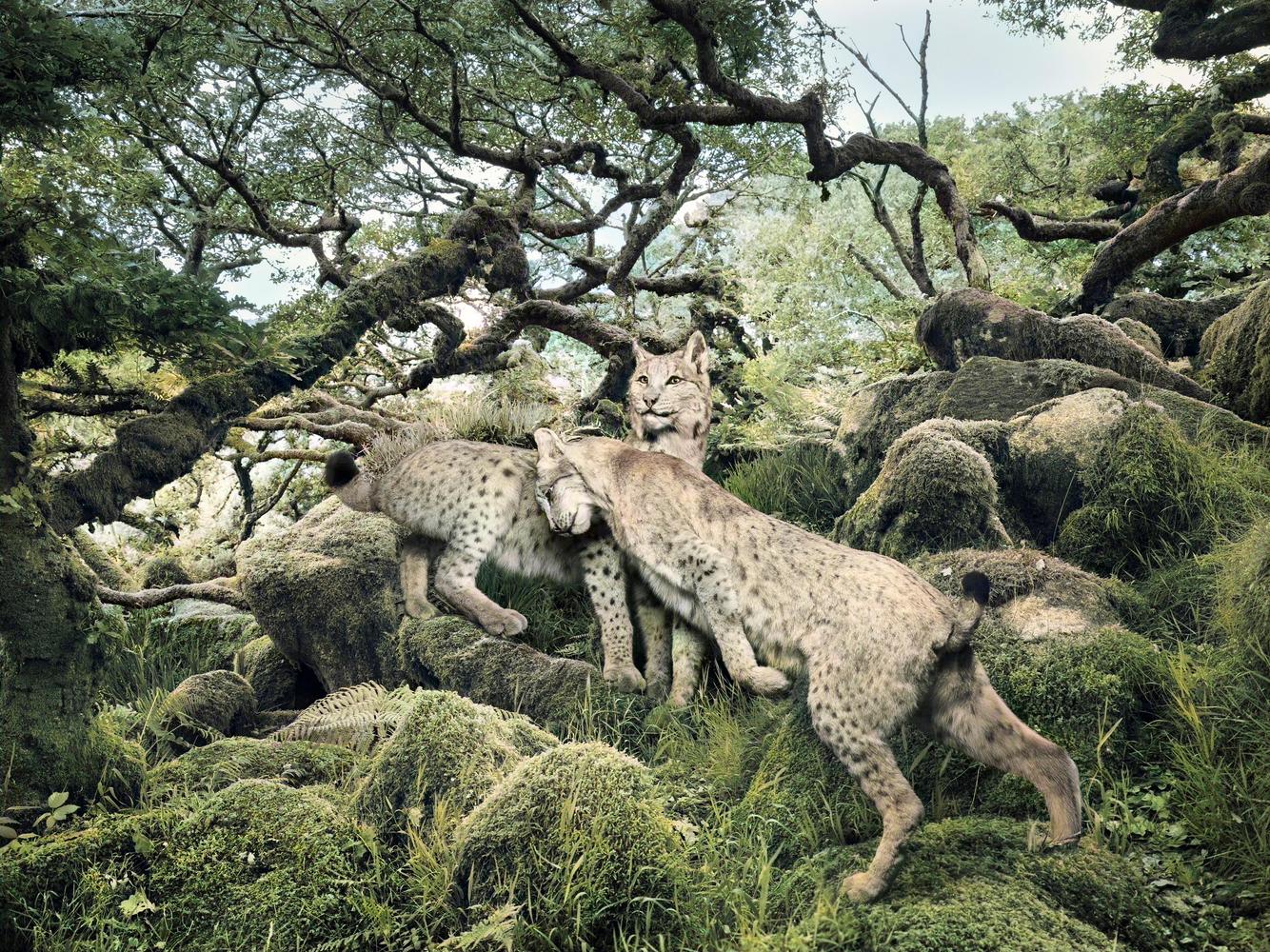

Photographer Jim Naughten has worked in the Scottish bogs for years, and his work for this series is a striking reimagining of the region's lost natural history. Naughten’s images combine photography of the rugged Scottish landscape with photographs of the extinct animals taken at natural history museums to depict species long absent from the Highlands, such as wolves, bears and lynx.

The moose was a common sight across Britain before disappearing 8000 years ago — another victim of human hunting and habitat loss. Today’s Scottish highlands no longer support the rich and varied wildlife it once did when the moose lived alongside aurochs, wolves and lynx. I hope that by creating an image of these majestic creatures, pictured back home in its original habitat, it may help us to imagine sharing this space with the natural world once again.

Muskox were common ice age mega fauna until the Holocene extinction event (otherwise known as the Anthropocene extinction), with the last known European population dying out 9000 years ago. Other ice age mega fauna, including woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, polar bear, lemming and Artic fox disappeared alongside the Muskox.

The brown bear was present in Scotland until the 10th century, but hunting, persecution and habitat loss eventually led to its extinction. This image relocates Ursos Arctos in the highlands, once forested and filled with an abundance of wildlife.

While the mountains retain a rugged beauty, they are a tinged with a sense of melancholy and loss. Thankfully awareness is growing and re-wilding projects are gaining much needed momentum.

While it very unlikely bears will be introduced to the UK, a growing understanding of ecosystems and tropic cascades should help us give space to the natural world.

Elk disappeared 8000 years ago, hunted to extinction for their meat and skins. They once shared forests with roe deer, aurochs and wild cats.

Scotland became spectacularly deforested, reduced to just 4% woodland cover by the late 18th century, so there was no option for Elk to eat their diet of willow, birch and aspen.

Lynx survived in Scotland until finally going extinct around 1300 years ago due to hunting and habitat loss. The youngest bone found is 1500 years old. There are very good arguments for the reintroduction of Lynx to the Scottish highlands, which now lack any apex predator and suffer from an overpopulation of red deer. They are shy, reclusive animals which would be very unlikely to come into contact with humans, but would likely bring tourists to the highlands whilst reducing red deer numbers, in a win for both human populations and the entire ecosystem. It would likely be the only apex predator to be introduced to the highlands.

Wolves were persecuted until their extinction in 1760. They survived longer than the lynx as they were less reliant on forests and thrived on red deer which had adapted to the open moors.

There have been calls to reintroduce the wolf in carefully controlled colonies, particularly to help with the 350,000 red deer that cause enormous damage to the ecosystem, but sadly Scottish National Heritage have shelved the idea following an outcry from sheep farmers.