Raise awareness for why people need sharks

For 400 million years, sharks have roamed every ocean on Earth. Few species have thrived on our planet for as long — and even fewer have been as misunderstood. The truth is that these mysterious, magnificent apex predators are essential to keeping the balance of marine ecosystems — and in many communities, help boost local economies. Sink your teeth into shark facts —and learn why people need sharks.

Share these facts about sharks:

Shark tourism generates more than US$ 300 million annually1

Sharks boost local economies through ecotourism. Over the last few decades, public fascination with sharks has supported businesses like boat rentals and diving companies in places such as the Bahamas, South Africa and the Galápagos Islands. These activities are said to provide 10,000 direct jobs globally.

Humans kill up to 100 million sharks per year2

Despite their scary reputation, most sharks are not dangerous to humans — in fact, they rarely attack people. If anything, sharks should be afraid of humans — many species of sharks are threatened by human activities. Sharks worldwide are the target of vast overfishing to supply the enormous demand for sharkfin soup, a delicacy in some Asian countries. But there is a flip side.

The largest sharks are nearly 60 feet long

Whale sharks — docile filter-feeders that passively scoop up small fish, invertebrates and plankton — can get up to 59 feet (18 meters) long.3 That makes them the largest sharks — and fish — in the world.4 By comparison, whale sharks’ fearsome cousins, great whites, can grow to about 23 feet (7 meters).

Shark behavior changes when the moon is full

A study of grey reef sharks in Palau, Micronesia, showed that sharks dive deeper during a full moon than at any other time in the lunar cycle.5 This “lunatic” behavior is thought to be tied to similar diving behavior exhibited by the shark’s prey — meaning that sharks are following their food source.

Hammerheads can see in 360 degrees6

Thanks to their oddly shaped heads and the unusually wide distance between their eyes, hammerhead sharks possess excellent binocular vision, enabling them to gauge both depth and distance when scanning the sea for their next meal. What’s more, by waggling their heads back and forth, they can spot prey (or danger) all around them — above, below and even behind.

Sharks were around before the first trees

According to the fossil record, sharks have been patrolling Earth's oceans for at least the last 400 million years7, with some estimates dating back 450 million years.8 That makes them slightly older than trees, which appeared on Earth about 390 million years ago.9

90% of all sharks died off 19 million years ago

Having survived at least four global extinction events — including the one 65 million years ago that wiped out the dinosaurs — sharks were nearly lost for good 19 million years ago. While the nature of this mysterious die-off event — what caused it and why it didn’t affect all species around the globe — begs further study, the fossil record shows that worldwide shark numbers dropped by 90 percent and up to 70 percent of all shark species were lost.10

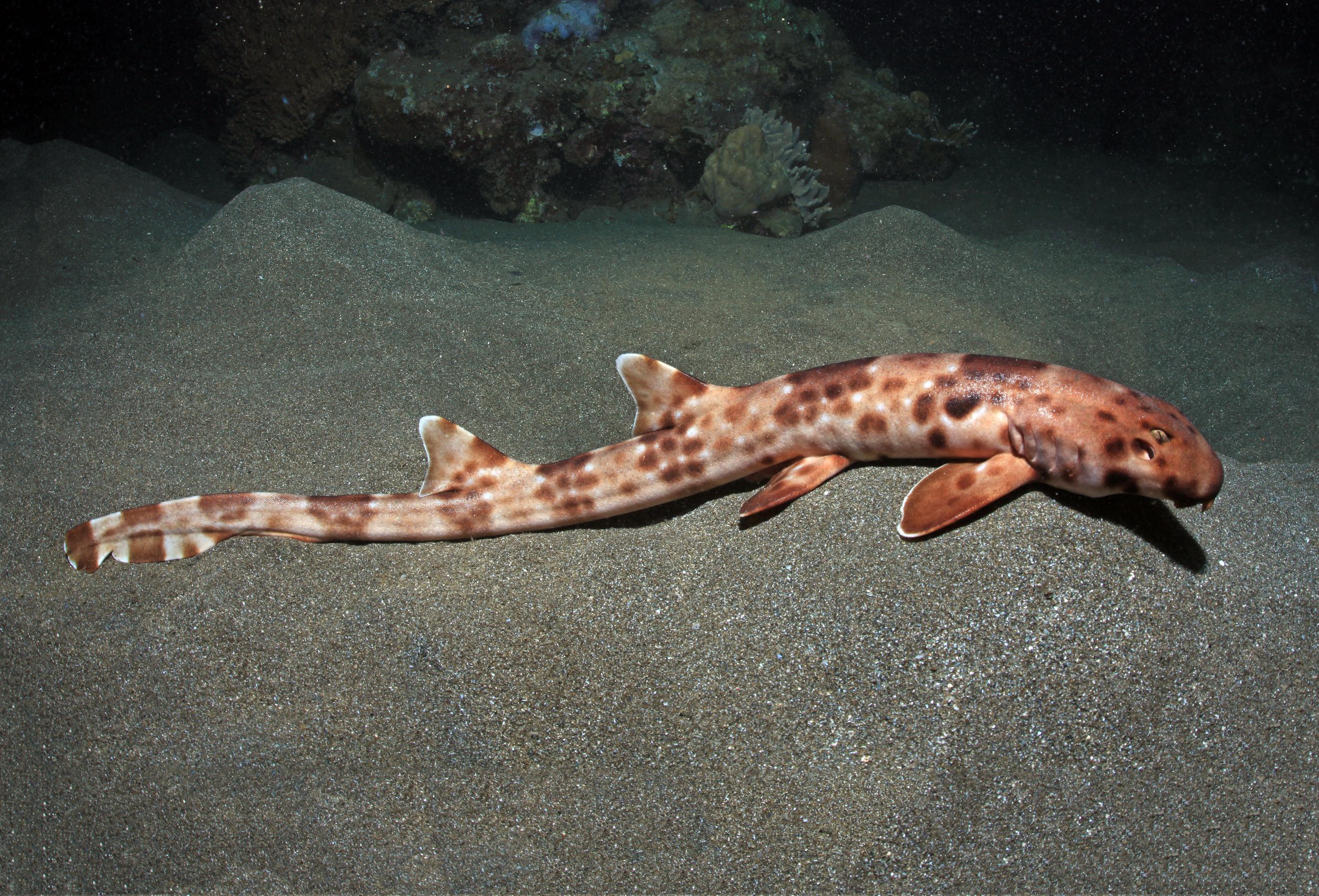

Some sharks can walk on dry land

Epaulette sharks, sometimes known as ‘walking sharks,’ can use their fore fins to amble across the beach — up to 100 feet (30 meters)11 — in search of crabs and other creatures left behind by the retreating tide. And there’s no rush: These sharks can survive for up to an hour outside of the water.

A great white’s bite force is nearly 25 times stronger than the average human’s

Bite force measures how strongly an animal can clamp down on its prey. In humans, the average bite force is about 160 pounds per square inch. For great white sharks, researchers estimate a whopping 4,000 pounds per square inch.12 While no sea creature chomps down harder than the great white, there is one on land: the Nile crocodile, with a crushing bite of 5,000 pounds per square inch.

Sharks are always growing new teeth

Because they are lightly anchored in a jaw made of cartilage rather than bone, shark teeth can come loose, especially during attacks on prey. A great white shark can lose up to 35,000 teeth in its lifetime.13 But sharks never stop growing new teeth. They have multiple rows of teeth in their jaws. So, when a tooth is shed it is replaced — in as little as 24 hours — by a new one, which moves forward to replace it — like a biological conveyor belt.

Shortfin makos are the fastest sharks in the world

These sleek, streamlined hunters can reach speeds of 50 miles per hour (80 kilometers per hour)14, though some estimates put that number closer to 62 mph (100 km/h).15 Either way, that’s much faster than any human can manage: Top Olympic swimmers can motor through the water at only about 5 mph (8 km/h).16

Greenland sharks are the slowest sharks in the world

Also known as ‘sleeper sharks” due to their laggardly nature, Greenland sharks cruise the chilly waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic at about 0.76 miles per hour (0.34 meters per second) — with bursts up to 1.7 mph (0.74 m/s).17 This is much slower than their top prey, the Arctic seal, so scientists surmise the sharks likely wait until the seals are asleep before attacking.

Greenland sharks will outlive us all

Greenland sharks aren’t just slow — they can live for centuries. In fact, scientists estimate their life span is at least 272 years18, making them the longest-living vertebrates known to science.

Sharks have a shocking sixth sense

Part of what makes sharks such effective hunters is their ability to sense the minute electrical fields that every living creature emits. Special, electrically sensitive organs called ampullae of Lorenzini allow sharks (and skates and rays) to detect very faint electric charges. Great whites can sense a charge as weak as one millionth of volt19 — helping them zero in on prey that they can’t see or even smell.

Nurse sharks have a cheeky way of breathing

Some of the more recognizable shark species — great white, tiger and whale sharks, to name just a few — risk suffocation if they remain still too long. That’s why they’re always on the move, drawing water over their gills so they can breathe. Other species, like nurse sharks or wobbegongs, pull water through their mouths and across their gills with a technique called “buccal pumping,”20 which allows them to remain motionless for long periods of time and ambush their prey.

Related content

References

- Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Barnes-Mauthe, M., Al-Abdulrazzak, D., Navarro-Holm, E., & Sumaila, U. R. (2013). Global economic value of shark ecotourism: implications for conservation. In Oryx (Vol. 47, Issue 3, pp. 381–388). Cambridge University Press (CUP). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0030605312001718

- Worm, B., Davis, B., Kettemer, L., Ward-Paige, C. A., Chapman, D., Heithaus, M. R., Kessel, S. T., & Gruber, S. H. (2013). Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. In Marine Policy (Vol. 40, pp. 194–204). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.034

- McClain CR, Balk MA, Benfield MC, Branch TA, Chen C, Cosgrove J, Dove ADM, Gaskins L, Helm RR, Hochberg FG, Lee FB, Marshall A, McMurray SE, Schanche C, Stone SN, Thaler AD. 2015. Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3:e715 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.715

- Osterloff, E. Whale sharks: Meet the world’s biggest shark. Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/whale-sharks-worlds-biggest-shark.html

- Vianna, G. M. S., Meekan, M. G., Meeuwig, J. J., & Speed, C. W. (2013). Environmental Influences on Patterns of Vertical Movement and Site Fidelity of Grey Reef Sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) at Aggregation Sites. In C. Fulton (Ed.), PLoS ONE (Vol. 8, Issue 4, p. e60331). Public Library of Science (PLoS). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060331

- McComb, D. M., Tricas, T. C., & Kajiura, S. M. (2009). Enhanced visual fields in hammerhead sharks. In Journal of Experimental Biology (Vol. 212, Issue 24, pp. 4010–4018). The Company of Biologists. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.032615

- Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. (Retrieved: 2023, November 17). The Evolution of Elasmobranchs (Sharks, Rays and Skates). http://www.pelagic.org/biology/evolution.html

- Davis, J. Shark evolution: a 450 million year timeline. Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/shark-evolution-a-450-million-year-timeline.html

- Dhar, M. When did Earth’s first forests emerge? Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/when-did-first-forests-emerge

- Sibert, E. C., & Rubin, L. D. (2021). An early Miocene extinction in pelagic sharks. In Science (Vol. 372, Issue 6546, pp. 1105–1107). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz3549

- Whitcomb, I. ‘Walking sharks’ caught on video, astound scientists. Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/walking-sharks

- Spanner, H. Top 10: Which animals have the strongest bite? BBC Science Focus. https://www.sciencefocus.com/nature/top-10-which-animals-have-the-strongest-bite

- Stokes, D. How Many Teeth Do Sharks Have? Dutch Shark Society. https://www.dutchsharksociety.org/how-many-teeth-do-sharks-have/

- Hoseck, N. What’s The Fastest Shark In The World? Dutch Shark Society. https://www.dutchsharksociety.org/whats-the-fastest-shark/

- Lang, A. W. (2020). The speedy secret of shark skin. In Physics Today (Vol. 73, Issue 4, pp. 58–59). AIP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1063/pt.3.4460

- Moss, D. Of Interest: How Fast Are Human Swimmers Compared to Other Species? Physical Education Update. https://www.physicaleducationupdate.com/public/Of_Interest_How_Fast_Are

_Human_Swimmers_Compared_to_Other_Species.cfm - Watanabe, Y. Y., Lydersen, C., Fisk, A. T., & Kovacs, K. M. (2012). The slowest fish: Swim speed and tail-beat frequency of Greenland sharks. In Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology (Vols. 426–427, pp. 5–11). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2012.04.021

- Nielsen, J., Hedeholm, R. B., Heinemeier, J., Bushnell, P. G., Christiansen, J. S., Olsen, J., Ramsey, C. B., Brill, R. W., Simon, M., Steffensen, K. F., & Steffensen, J. F. (2016). Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark ( Somniosus microcephalus). In Science (Vol. 353, Issue 6300, pp. 702–704). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf1703

- King, B., Long, J. How sharks and other animals evolved electroreception to find their prey Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2018-02-sharks-animals-evolved-electroreception-theirprey.html

- Matthias, M. Do Sharks Really Die if They Stop Swimming? Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/story/do-sharks-really-die-if-they-stop-swimming