Off Mexico's Yucatán coast, a road connects a small fishing community's slender islet to the mainland.

On one side of the road sits a healthy mangrove forest teeming with wildlife.

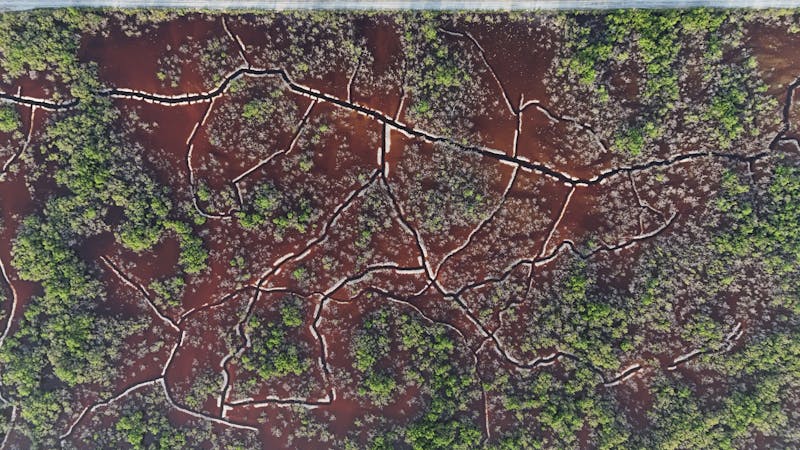

On the other side of the road: bare dirt, pocked with patchy stands of mangrove trees.

In the 1990s, construction of the road to Isla Arena cut off the flow of water from underground rivers to one side of the mangrove forest, depriving these coast-hugging trees of the unique conditions they need to thrive and proving deadly for the wildlife and fish they supported.

The road leading to Isla Arena separates the mangrove forest, depriving one side of the flow of water.

But look closely today, and signs of life are beginning to reappear.

With support from Conservation International, flamingos have been spotted feeding in the degraded mangrove forest after a years-long absence, indicating the return of key species like fish and crustaceans.

Flamingos feeding on fish and crustaceans are a sign the mangrove forest is beginning to recover.

To bring them back, the community is digging channels — by hand — to restore the flow of water and restore a thriving mangrove ecosystem.

It’s back-breaking work, but their efforts are paying off: So far, locals have opened roughly 9 kilometers (6 miles) of tidal channels, sometimes digging up to their necks in water.

“When we started the ditches, we thought we wouldn't be able to handle the work because it looked tough,” said Idelfonso Rivera, a community member who works on the restoration project. “But the more we opened up the river, the more life appeared. Before you couldn't cross it, and now we have the joy of … a clean river, when before it was a dump.”

Community members have dug roughly 9 kilometers (6 miles) of channels, so far.

Isla Arena, a fishing community of less 1,000 people, is no stranger to the challenges that afflict many similar communities that depend on nature for their lives and livelihoods. But the road — essential to connecting the islanders to the mainland — came at a steep price to the environment that nurtures the fish that islanders depend on.

In the Yucatán Peninsula, rivers are underground. Construction of the road transformed that ecosystem: Salinity levels, water temperature and chemical concentrations of sulfates, which can cause acidification of the water and is deadly for fish and mangroves, skyrocketed from the lack of flowing water.

“The area became inhospitable to wildlife,” said Asis Alcocer, ocean expert at Conservation International-México. “With the ecosystem so out of balance, our only hope was to restore the flow of water by digging the channels.”

By restoring this balance, the project is aiming for natural regeneration of mangroves, with more than 30,000 red mangroves being planted to jump-start the process, Alcocer said. The project’s success hinges on the re-establishment of the mangrove forest and restoration of the water flow.

“Mangroves act as nurseries for all kinds of wildlife, including fish and crabs — their decline is absolutely connected to the decline in these species’ populations,” he said. “In addition, mangroves act as a buffer against extreme storms, which in a place prone to hurricanes like the Yucatán is critical."

The community has planted roughly 30,000 mangrove seedlings along the channels.

As the conditions show signs of improvement, the community is witnessing the direct link between a healthy mangrove ecosystem and their well-being and economic opportunities, said Norma Arce, a biologist at Conservation International-México and the project lead.

“The decline in fish has affected the community’s livelihood in a profound way,” she said. “At the start of the project, the community was understandably skeptical, but by directly engaging them in the process, we’ve built a level of trust that is helping the project flourish, while also supporting their needs.”

Last year, Conservation International-México and the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas began hosting workshops to train locals on mangrove restoration. In addition to digging the channels, locals are involved in all the technical work on the project, including monitoring wildlife, soil and water quality. Restoring the mangroves also opens the door to ecotourism opportunities, such as birdwatching, as the area is a migratory bird hotspot.

“Before, we knew nothing about the mangroves and how they benefited us," said Zugey Cruz, a community member who works on the project. “When we entered the site, it was a dry place; this work has helped us a lot. Now we see that it has the fluidity of water, as the conditions of the mangrove should be."

As the mangrove forest conditions improve, community members say they see a direct link between its health and their well-being.

Women have been especially engaged in the project, Arce said.

“In the past, women weren’t invited to participate in projects like this because they weren’t considered strong enough,” she said. “They’re proving that mentality wrong. The work is giving them confidence and showing that they are stronger than they thought they were.”

Over the next couple of years, the project plans to more than double the restoration area from 217 hectares (536 acres) to more than 500 hectares (1,235 acres). Given the community’s fishing identity, the next phase also plans to help promote sustainable fisheries and sustainable activities like mangrove honey and ecotourism.

The effects of climate change compound the challenge facing the community, disrupting fish catches while increasing risks from extreme flooding and hurricanes, Arce said. Just last year, a powerful hurricane swept through the area, but the mangroves and the channels held on, buffering the community from the storm’s worst impacts.

“Mangroves will become even more important as climate change accelerates,” she said. “In just a few short years since the project began, we’ve seen significant improvements. While full restoration will take many years, this gives us hope."

Isla Arena on Mexico's Yucatán coast.

Mary Kate McCoy is a staff writer at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.