So — there was another climate report?

Yes. Specifically, the “Working Group III contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC.” Trips right off the tongue, doesn’t it?

Not at all. Remind me who the ‘IPCC’ is?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a body of the United Nations. Thousands of scientists contribute to their reports. Collectively, the IPCC is the global science nerd authority on climate change.

So why are there so many of these reports?

Because climate change is a BIG topic. Different groups of scientists contribute their research and expertise on various climate-related topics. This latest report is about how we are performing in mitigating climate change, and what we can do to up our game.

OK. I saw some news about it. What did it say?

It said plenty of things, but the news that you may have seen was that humanity is not on track to keep climate change within the 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) “safe zone” — and that to change course to get there, well, we’re just about out of time.

What I read makes it sound like we’re all doomed.

That’s understandable — the gloom was on full display in the news and social media. One prominent climate activist called the report “absolutely harrowing.” One scientist reported having a “full-blown panic attack” during the IPCC’s press conference. And the UN Secretary General himself — with almost artless candor — took aim at world leaders, calling the report a “file of shame” full of “empty promises.”

Sheesh. That’s really depressing!

You’re not alone in feeling that way.

“Yeah, it is definitely depressing,” says Bronson Griscom, a climate scientist at Conservation International who contributed to the latest IPCC report. “We have not been anywhere close to the trajectory we needed to be on.”

“And guess what? We’re still not. Not only are countries not achieving their commitments to the Paris Agreement — even if they were, those commitments aren’t even sufficient to solve our problem.”

Great … now I feel even worse.

Sorry. There’s no sense in denying the gravity of the problem, though.

I’m not denying it. I accept that climate change is happening. It just makes me sad.

Yes, it is saddening. And it’s actually really important to acknowledge our feelings about it. As we wrote a few years back, climate change can elicit “a kind of dread that makes you just want to stop thinking about it.” So, it’s commendable that you’re confronting these feelings.

And now that that’s out of the way, we can start talking about more exciting stuff.

‘Exciting stuff’?

“It’s high time we get past the denial stage of accepting depressing news,” Griscom says. “Once we work through that, that’s where we get to the exciting side of the story.”

That — once you get past the legitimately terrible news — is what this new IPCC report gets at.

All right, I’m listening. What else does the report say?

The report affirms something we’ve long known: that nature remains among the most effective (and cost-effective!) climate solutions.

And the report also reaches a new level of consensus on the numbers, and the set of actions we can take.

Like what?

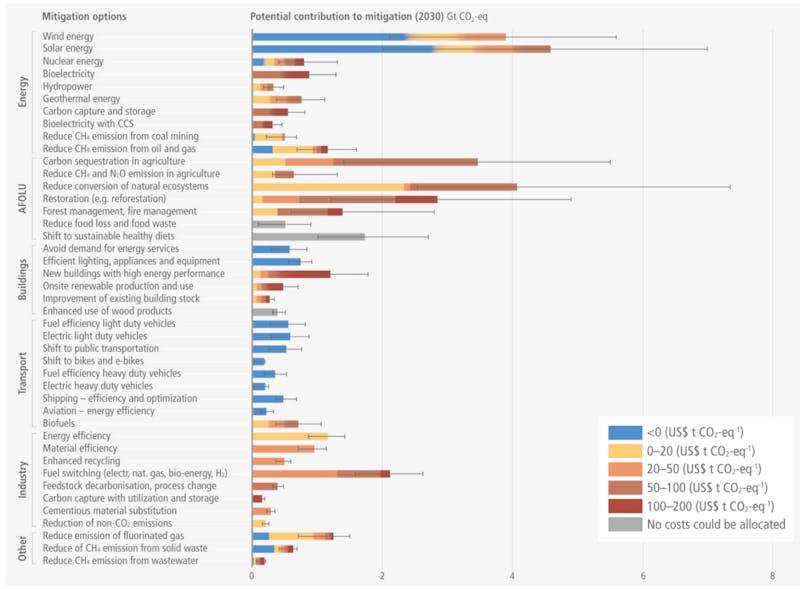

One graph in the report lists 43 different options for cutting greenhouse-gas emissions by 2030 — options in the energy sector, transport, land use, industry and more. If all the actions are taken to the extent possible, the report indicates, we would reverse the climate crisis — and likely stabilize well below 2C (3.7F) of warming, beyond which life on Earth starts to get ugly.

Here’s that graphic, by the way:

What it shows is that three actions — reducing the destruction of forests and other ecosystems; restoring those ecosystems; and improving the management of working lands, such as farms — are among the top five most effective strategies for cutting carbon pollution. Simply not cutting down forests is the second-most effective action we can take to curb emissions (scaling up solar energy is No. 1, in case you were wondering).

That’s good, I guess?

Are you kidding? It’s extremely heartening. This says that not only is large-scale protection and restoration of nature an option that we can still take, but if we do it, we will see a major effect on our climate.

And the benefits wouldn’t stop there.

What do you mean?

Because protecting nature comes with a whole host of side effects. Look no further than the Sustainable Development Goals.

What are those?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a series of 17 global goals established in 2015 to essentially make the world a better and more just place. They cover things like reducing poverty, hunger and inequality; improving education, health and access to clean water, and so on.

As it happens, protecting and restoring nature is necessary to achieve most of the SDGs, a 2021 study by Conservation International found. In other words, nature conservation can directly and materially improve the lives of billions of people around the world.

“When we protect and restore nature to stabilize our climate, we’re also supporting communities that rely on nature daily,” Griscom says. “This is critical because those communities are disproportionately impacted by climate change, yet bear the least responsibility for it. So there’s a justice aspect to all this.”

“If we do this,” he says, “we are not just solving an emerging problem actually can make the world a lot better than it is.”

I didn’t know that.

Not surprising — it’s not getting talked about a lot! That is, unless you listen to our scientists, who are pretty excited at the possibilities in spite of the gloomy nature of this work:

“It’s just really exciting that scientifically speaking, there are all kinds of these ‘win-win’ alignments between the SDGs, which are about social justice and development, and climate solutions,” Griscom says. “Leaning into climate mitigation will actually deliver a bunch of additional benefits that will help make a healthier and more just world for all. It’s really freaking exciting.”

(Can you tell he’s excited?)

Indeed. So — how do we do this, then? How do we protect nature on a big enough scale?

Whoa. We don’t have time to go too deep into that. But the most effective methods of nature conservation — that is, methods that you can scale up and replicate elsewhere — generally include:

- Create and expand protected areas (e.g. national parks) — and don’t roll them back.

- Support Indigenous peoples to have their traditional lands legally titled to them — there are no better stewards of healthy high-carbon ecosystems, and here’s why. (Oh, also — it’s their land anyway.)

- Support farmers, ranchers and loggers with incentives, training and regulations to better manage their lands. Most of these land stewards want to do the right thing, but they need help doing it.

- Demonstrate the value of the benefits that nature provides, thus encouraging people to take better care of it.

- Make carbon markets work better to protect forests, which can reduce carbon that is emitted elsewhere.

Carbon markets, as in offsets? I’ve heard about those.

Yes, we’ve talked about those before. Carbon offsets are one mechanism that can move quickly to reduce — and, ultimately, remove — carbon from the atmosphere, something that the IPCC report says we need to do as soon as possible.

I think I know how offsets work, but maybe you can remind me.

Sure. Forests absorb climate-warming carbon from the atmosphere — carbon that humans have been dumping into the air at an ever-faster pace. The idea behind offsets is that by paying to protect forests, you can help to balance out carbon emissions made somewhere else.

Got it. But not in a way that allows people to just keep polluting, right?

Precisely — done right, offsets make emissions reductions this decade much less expensive.

“We’re not going to stop flying airplanes,” Griscom says. “We all know people are still going to fly. We all know that there is not an electric airplane available. So: How do you deal with that? You deploy things that are feasible and that we can actually afford, such as asking folks who fly to pay for restoration of ecosystems to remove more carbon than the airplanes emit.”

I read that some people are really against offsets.

“People need to get over their puritanical hang-ups with offsetting,” Griscom says. “Are we going to develop some massive machine that sucks carbon out of the air in a way that anyone can afford? I hope so. But guess what? We don’t have one of those right now,” he says. “But we do have trees now. The largest and only mature form of carbon dioxide removal is nature. This is clear in the IPCC report.”

So speaking of things we can afford: How much is all this nature protection going to cost?

We’re glad you asked: The report finds that protecting nature to help limit global warming to less than 2°C (3.6°F) would cost up to US$ 400 billion a year by 2050.

That seems like a lot of money.

It’s not, really.

But won’t that, like, hurt the economy?

On the contrary, it will help the economy, because climate change will cost more if we stand by and do nothing. And besides, as Griscom points out, it’s less than the current subsidies provided to agriculture and forestry — many of which are pushing farmers, ranchers and loggers in the wrong direction.

In any case, it’s a case of pay up now, or pay more later: “Overall, the global economic benefits of limiting warming to 2°C likely exceed the mitigation costs,” Griscom says. “And that’s not even factoring in loads of economic benefits of protecting and restoring nature, like clean water, flood control and healthy fisheries.”

Wait — you said earlier that the ‘safe zone’ was 1.5C, and now we’re talking about 2C. Does that mean that 1.5C is not going to happen?

Let’s bring in the scientist for this one.

“In 1968, if you had asked me if we would get to the moon, I would have said, no freaking way,” Griscom says. “And we got to the moon.”

“Is it reasonable to predict changing society to get to 1.5 based on the way things are going now? People would say no, it seems kind of crazy. But do I think that societies can transform at the rate required to get there? Yes!”

So … can we do this?

As a species, our backs are up against the wall, Griscom says: “If we don’t turn the corner in this decade, it will be physically impossible to do later.”

“It will require a major transformation of society,” he says. “We’ve reached a critical point in the conversation … this report is not speaking politely — it’s shaking us by the collar. And when a bunch of nerds start shouting, it’s time to listen, take a deep breath and act.”

“It’s game time. We need to do everything we can, right now.”

Bronson Griscom is the senior director of natural climate solutions at Conservation International. Bruno Vander Velde is the managing director of content at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates here. Donate to Conservation International here.

Cover image: Sunrise in Peru (© Benjamin Drummond)